AGRICULTURAL PESTICIDES

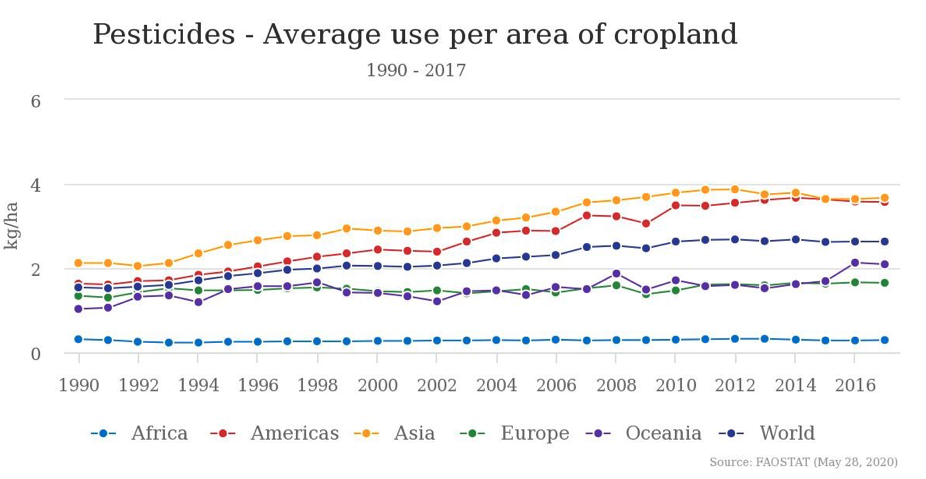

Agricultural production is the primary economic driver for much of Asia. The benefits of a farming economy are incalculable, as this activity supports the livelihood of a majority of 75 percent of rural poor throughout developing regions of the world (including much of the Asia-Pacific region). Agriculture also provides local, regional, and global food security for people all throughout the world. As large swaths of Asia-Pacific, especially Southeast Asia continue to develop, and become more urbanised the increasing population growth trend for the region has, and continues to require higher agricultural outputs to keep up with food demand. This realisation throughout East, South, and Southeast Asia has led national and regional governments to pivot from subsistence farming to a commercial-based agricultural model; one driven by the goal of increasing the productivity of crops and livestock per unit input of utilised land area. This region-wide policy shift, in turn has created economic demand, and use of more and more agri-chemicals specifically pesticides as one way of protecting crop yield. The effect of industrialised agricultural economies throughout Asia are particularly stark with regards to pesticides use for the region. The chart below was accessed from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and shows that the entire Asia region from 1990-2017 consistently topped all other world regions in terms of total average pesticides use per area of crop land.

East and Southeast Asia as a region is especially dependent on large-scale pesticides use for crop management. The geographic information depiction below was accessed from the FAO website database, and shows China, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, and Taiwan as regional jurisdictions with the highest pesticides inputs followed by Brunei, Thailand and Viet Nam, then Myanmar. Lao PDR and Indonesia show comparatively lower pesticides input use. (There was insufficient data for Cambodia and the Philippines).

Agricultural pesticides are proven to protect crops, but the empirical weight-of-evidence demonstrates that the health and ecological risks highly outweigh the benefits, particularly with respect to long-term effects.

The concern associated with large-scale pesticides use is multi-fold. 1) Many toxic-to-highly toxic pesticides almost always escape the immediate application area where it moves as aerial drift, runoff into surface water, seepage into the soil, and sometimes reaching the groundwater table creating potentially multiple human environmental exposure pathways, and resulting in “non-target” ecological impacts, 2) A continually growing body of scientific research evidence strongly points to agricultural pesticides use leading to both acute and long-term environmental and public health consequences particularly among children, and 3) agricultural workers (especially from low and middle-income developing countries) who are exposed to various types of pesticides on an annual basis show evidence of serious health outcomes after both short and long-term exposures; in an occupational setting not only does inherent chemical toxicity pose a concern, but in many cases limited or no training coupled with protective equipment deficiencies exacerbate potential exposures from crop applications.

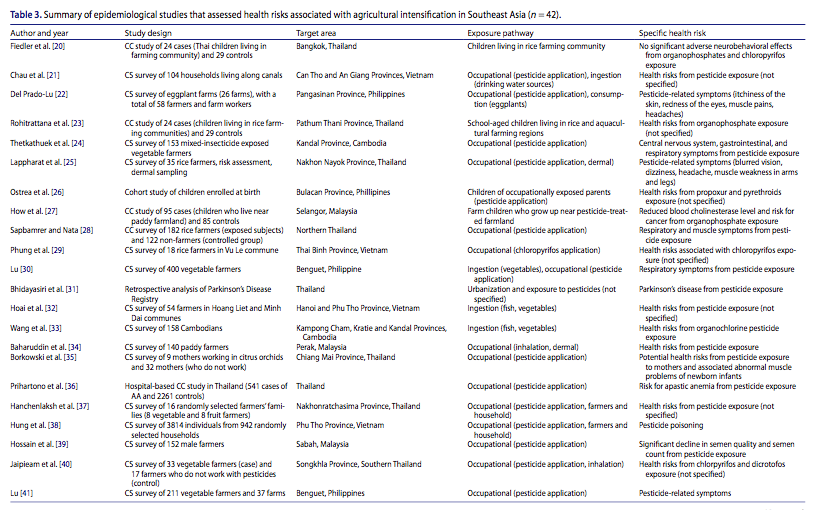

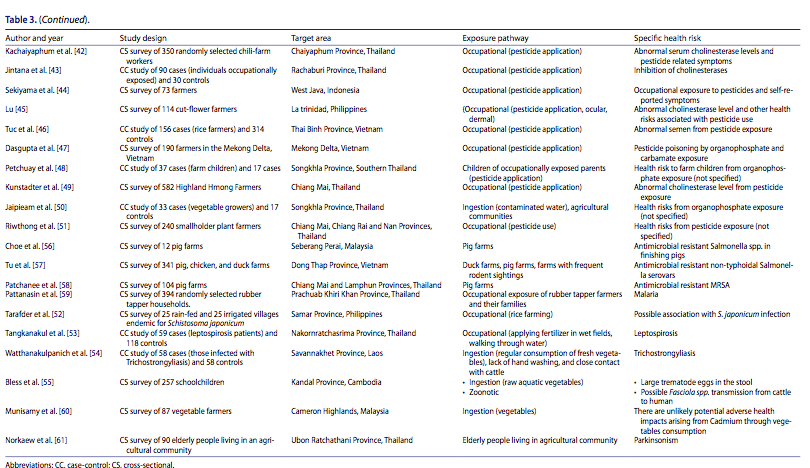

In Southeast Asia pesticides drift from crop applications migrated to early-years schools of neighboring villages and towns in Malaysia, Viet Nam, and Cambodia that led to high profile children’s pesticides poisoning cases. From an occupational perspective one cross-sectional survey study of 182 rice farmers in Northern Thailand showed statistically significant increases in breathing difficulties and chest pain from pesticides application exposures (Lam et.al., 2017).* Risk from agricultural pesticides to the general public can occur from dermal exposures, intake of contaminated drinking water, or through detectable residues on fruits and vegetables. This was the case when Chinese kale sold at markets in Nakhon Pathom,Thailand contained residues of 12 types of farming pesticides (some of them highly toxic) among them Chlorpyrifos, Cypermethrin, and Carbofuran that exceeded regulatory MRLs (Lam et.al., 2017).* The table below is a compilation of epidemiological evidence associating agricultural pesticides use with various human and animal health risk (Lam et.al., 2017).*

* Lam S, Pham G, Nguyen-Viet H. Emerging health risks from agricultural intensification in Southeast Asia: a systemic review. Intl J. Occ Env Hlth; 23(3): 250-60. 2017. DOI10.1080/10773525.2018.1450923

Though intergovernmental agencies such as FAO have engaged in collaborative efforts to properly train farm workers about protocols for pesticides use reduction using Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategies, most nations throughout Southeast Asia for example have yet to shift towards a region-wide sustainable farming paradigm, possibly out of unwarranted fear of interfering with commercial crop outputs. Examples of this “fear” have been dispelled, for instance, by local growers who have increased crop yields with sustainable farming practices, all but eliminating chemical fertilisers and pesticides use in favour of crop rotation, and physical harvesting.**