ENVIRONMENTAL GOVERNANCE

Protecting public health and improving the quality of the natural environment are only as effective as the policies that are mandated by existing governance structures. In turn, only law and policy born out of social and cultural integrity for the benefit of its citizens, communities, and ecology will achieve those proper ends.

‘Good’ governance as broadly defined by western societies is the partnership and responsibilities between society and the state in establishing and implementing policy and process that serves to accomplish widely-accepted social goals. This concept is largely driven by fundamental principles of civic participation, equity, civility, accountability, and transparency visa vis representative or participatory democracy.

Historically political governance systems found in almost all East and Southeast Asian nations (to varying degrees) centre on a dominant centralised state where policy making falls under the purview of a deeply engrained bureaucratic structure with little to no public involvement. This type of system is born of a time-honoured patriarchal philosophy that assumes only a few know what is best for its citizenry. From an environmental perspective this governance paradigm has, and continues to hinder the full sustainability potential of societies throughout Asia-Pacific where essentially unfettered economic development holds precedence over all other socially relevant issues.

A pivot away from the centralised governance model that often has exclusive preference for business and corporate interests, and a cultural and political will for decentralising towards more balanced governance systems are logical needed steps to embracing the idea that people, consumers who support commercial and agricultural economies at local and regional levels should have access to environmental information; requisite knowledge that offers insight into the factors that may impact their health and well-being. Even without a change to decentralisation ASEAN governments could, for example consider implementing process changes that open more avenues for information transparency for the general public.

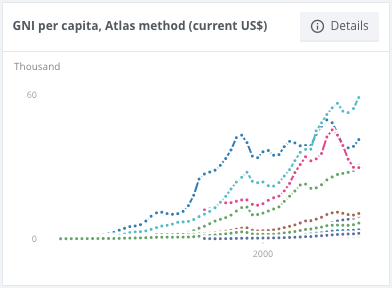

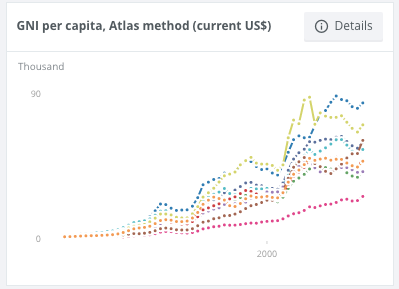

Developed societies are often indicated by more measured economic growth and development, higher average annual Gross National Income (GNI) per capita, and lower overall pollution emissions which also tie in with stronger more open governance systems. The charts below (courtesy of the World Bank website interactive database) show that the average GNI per capita for the top 10 nations with the highest level of environmental quality (according to the Yale Environmental Performance Index) exceeds the average GNI per capita for the collective East and Southeast Asian region (no data for Taiwan) by nearly 3.5-fold; a region that shows a markedly lower average index of performance based on select measures of environmental health and ecological vitality.

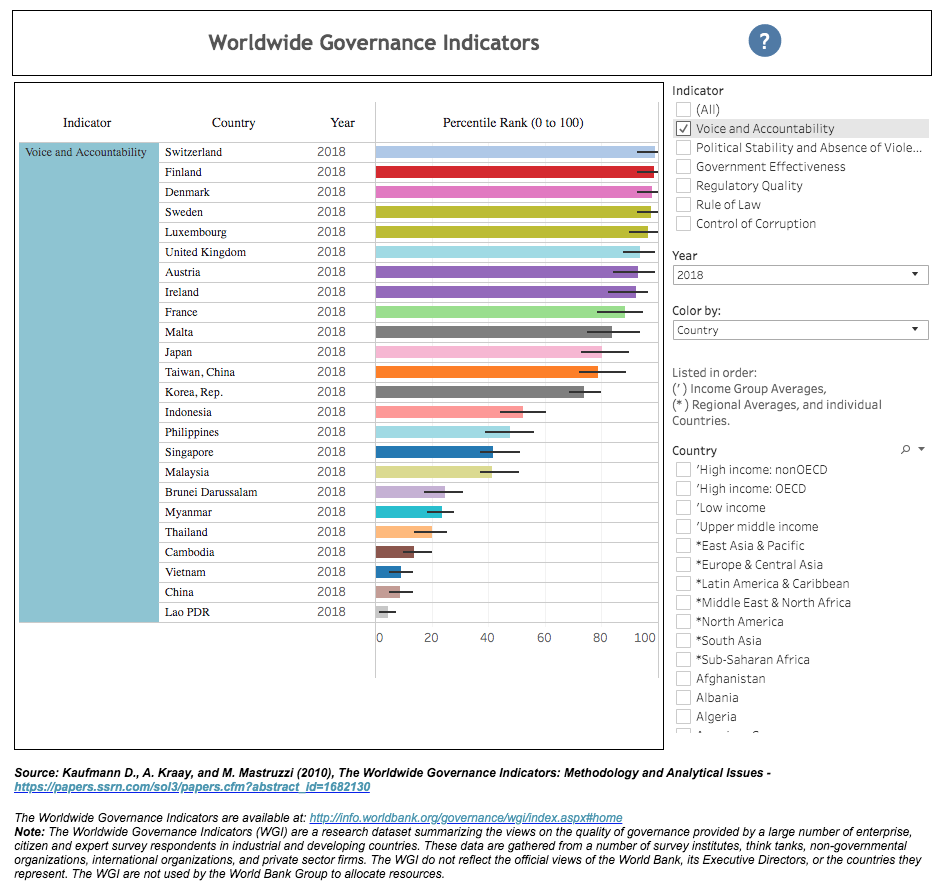

The World Bank’s empirically derived indicators measuring the strength and vitality of governance systems through 1) Voice and Accountability, 2) Political Stability, 3) Government Effectiveness, 4) Regulatory Quality, 5) Rule of Law, and 6) Control of Corruption demonstrate that eight of the top 10 nations with the highest index of environmental performance also score at least within the 75-90th percentile range (among the highest) indicating for healthy and robust governance structures. At the opposite end, the collective grouping of East and Southeast Asian countries (ASEAN jurisdictions in particular) that demonstrated an index of environmental performance mostly in the lowest tiers including, China, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand, and Viet Nam also scored among the lowest percentiles (0-50th) for governance.

Important to note is that out of the six world governance indicators only “Voice and Accountability” registered at the highest percentile ranges for all the countries scoring in the top 10 for environmental performance while again similarly China, Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand, and Viet Nam scored at the lowest percentile ranges for this indicator. The chart below (courtesy of the World Bank’s interactive World Governance Indicators database) demonstrates that the metric gauging information transparency and accountability to the public appear to be associated with having measurable influence on environmental outcomes.